Nearly everything you thought you knew about blue light, screens, and sleep is being upended—what if your nightly doomscroll isn’t the villain, but your clock-watching is?

Story Snapshot

- Recent research shows it’s total screen time before bed, not the specific activity or blue light alone, that disrupts sleep.

- Major studies in the US and Norway with over 160,000 participants challenge the assumption that social media is uniquely harmful at night.

- Scientists now emphasize the “time displacement” effect—screens simply steal the hours meant for sleep.

- New guidelines urge cutting all screen use 30–60 minutes before sleep, rather than targeting apps or content types.

Screen Time: The New Target in Sleep Science

Sleep scientists are rewriting the rulebook on nighttime screen use. Decades of finger-pointing at blue light and social media have given way to a simpler truth: the time you spend on screens after bedtime matters more than what you’re doing or which app you’re using. Studies published in 2025—one in JAMA Network Open analyzing 122,058 American adults and another in Frontiers in Psychiatry tracking 45,202 Norwegian students—found that each hour of screen use after going to bed led to 24 minutes less sleep and a 59% higher risk of insomnia. Social media, gaming, and streaming all fell under the same umbrella; none stood out as a worse offender.

Researchers have shifted focus from the color of the light or the content on your phone to a more practical culprit: time displacement. The more time spent staring at screens after you should be sleeping, the less time remains for actual rest. The Norwegian study’s lead author, Dr. Gunnhild Johnsen Hjetland, states, “The type of screen activity does not appear to matter as much as the overall time spent using screens in bed.” This turns the spotlight away from app designers and device manufacturers and back onto bedtime routines. Instead of waging war on TikTok or Netflix, the new frontline is the digital clock and notification settings.

The Rise and Fall of Blue Light Hysteria

Blue light became a household villain in the 2010s, with warnings about melatonin suppression and circadian sabotage. Public health campaigns shouted for screen-free bedrooms and night mode apps. Yet recent evidence suggests these efforts may have missed the forest for the trees. While blue light does delay melatonin release—making it harder to fall asleep—the relationship between screen use and sleep quality is more tangled than first believed. Content type, device brand, and even screen brightness have become supporting actors. The main plot twist: screens steal sleep mostly because people use them when they should be sleeping. The old narrative, which focused on what you watched or played, is being replaced by a hard look at how much you watch or play.

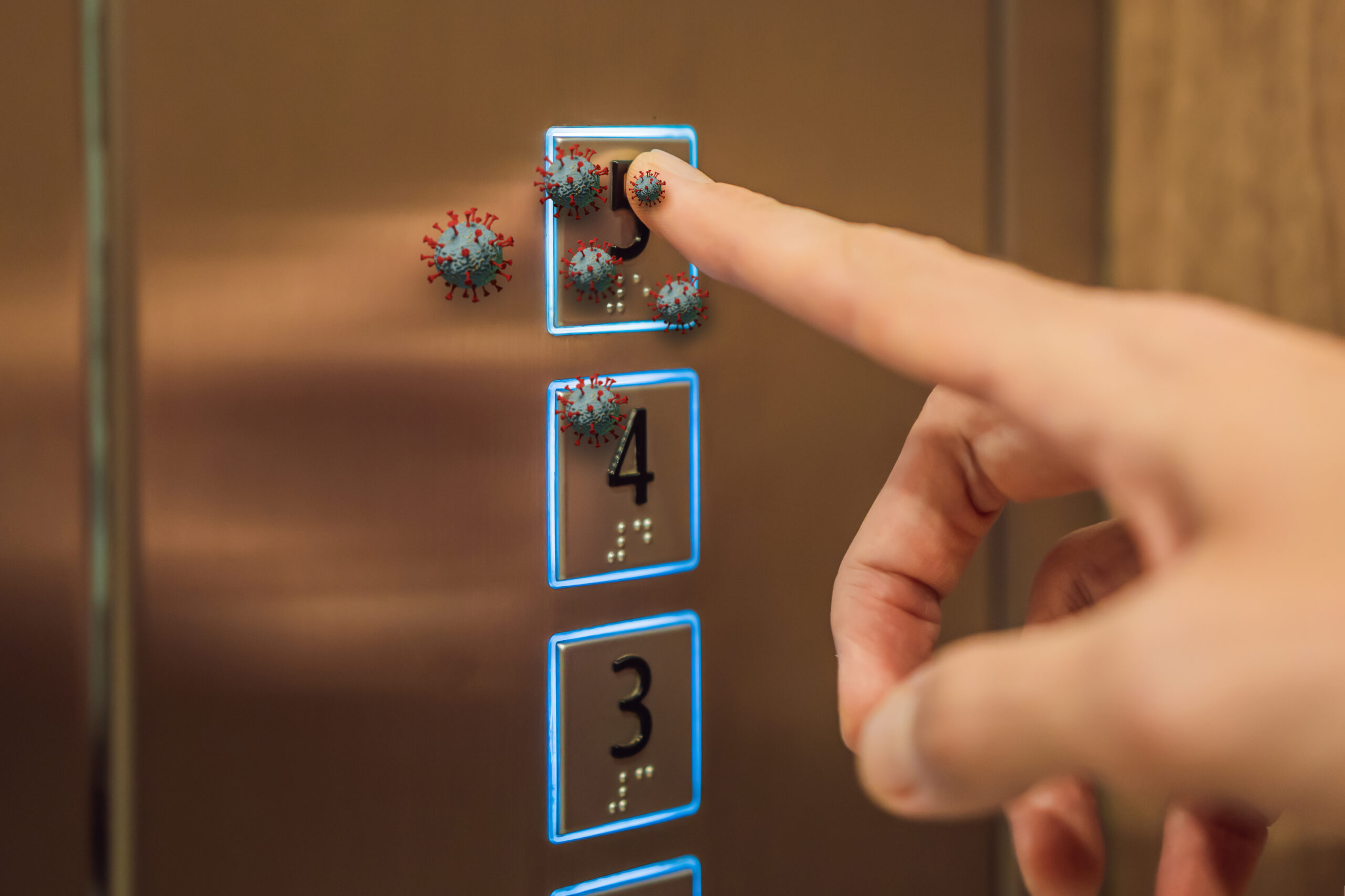

COVID-19 accelerated screen use, as both adults and adolescents spent more time online for work, learning, and socializing. Sleep disorders ticked upward, and researchers scrambled to untangle the causes. Large cohort studies began parsing data in unprecedented scale. Instead of finding smoking guns in specific apps or colors of light, they found that every minute on a screen after bedtime ate into total sleep duration—regardless of the digital distraction.

New Guidelines and Lingering Questions

With findings echoing across continents, sleep scientists now advise a universal approach: stop all screen use 30–60 minutes before sleep, and silence notifications. The American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study–3, and similar research in Norway, both recommend this blunt tactic. These new guidelines reflect a more nuanced understanding, acknowledging individual differences in chronotype, culture, and personal sleep needs. Technology companies may soon respond with smarter night modes and notification controls, but the advice is clear—less screen time after dusk equals more sleep.

Uncertainties remain. Some researchers caution that causality is not yet established: does screen use cause insomnia, or do insomniacs turn to screens out of boredom and frustration? Grouping all screen activities into one category may obscure subtler effects—for instance, whether gaming or chatting with friends has unique impacts. Cultural differences and personal habits complicate the picture. The call for more physiological, experimental studies is growing louder, but the message for now is simple: bedtime screens are sleep thieves, no matter the app.

Sources: